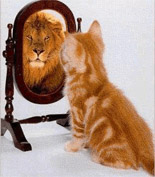

No, I’m not talking about the guy who lives in a van down by the river (Saturday Night Live). I’m referring to the type of person we’re all capable of becoming; the kind that is typically a much better hire; the kind you need to help develop in your organization.

Over the past 25 years of providing psychotherapy, my chief mission has been to free people from unconscious ruts that control their lives. This isn’t easy. People rarely see how they have boxed themselves into a view of themselves and a view of the world that limits their perspective, beliefs and actions.

Over the past 25 years of providing psychotherapy, my chief mission has been to free people from unconscious ruts that control their lives. This isn’t easy. People rarely see how they have boxed themselves into a view of themselves and a view of the world that limits their perspective, beliefs and actions.

When a person is in a rut, they limit their own movement, growth, vision and freedom to act. They see the world in a fixed way, and try to convince everyone around them that their “rut trapped” perspective is indeed reality. The way they lead their life unveils consistent themes, describing their own personal rut repeatedly acted out.

A person who is not stuck in a rut flows like a river, emanating wisdom, humor, and humility even in difficult times. They may have a long list of things that haven’t worked out, but have no regrets for their efforts.

When things are going well, economically and emotionally, it is much more difficult to differentiate the “rut people” from the “river people.” However, in these difficult times, ruts are bound to surface. Even the most fluid people can be temporarily thrown into a rut in these extreme circumstances, simply because life isn’t familiar or secure.

Losing a job, a home, and plans for the future can certainly appear as an insurmountable rut. “River people” however, don’t allow themselves to get stuck there. They manage to continually pull themselves up and out of the rut, dust themselves off, and move on with life. I feel fortunate to know many river people.

As leaders, you owe it to yourself and those you coach to help free them from their ruts. Whether you’re coaching or interviewing new candidates, help them find hope and envision the opportunities that can unfold if they exercise the “formula for confidence.” Help them realize their freedom and potential through new ideas, new innovations, new training, new commitments, new values, and perhaps even an entirely new direction.

You’ll find that everyone within an organization benefits once the individual tributaries find their “flow,” and can contribute their full potential once again. It’s not only practical to encourage this hope, it’s the right thing to do.

But, change is difficult – Most healthy, rational people avoid change, preferring instead the security and safety of what is known. Ironically however, change can produce incredible growth, if responded to effectively. If you’re interviewing new candidates without both empathy around change PLUS the encouragement to change, your missing an incredibly useful and helpful tool.

Have candidates answer this question: When have you experienced the most growth in your life? For most people the answer is when they were undergoing tremendous change, accompanied by uncertainty…perhaps when they were much younger.

It’s normal to risk more when we’re younger, because we don’t have that much to lose. If you analyze that statement, you will begin to see the problem: Security and hanging onto what we’ve acquired becomes paramount for most of us when we’re older. We cling to it and cherish it, without ever reflecting on its inherent value to our well-being.

Of course it’s irresponsible to take foolish risks. But, you can also make the argument that it is foolish to follow a course of action simply because it offers the illusion of security.

For some inspiration on becoming a manager who hires and develops “river people,” read and insert the word manager for friend in the below quote:

“A true friend (manager) knows your weaknesses but shows you your strengths; feels your fears but fortifies your faith; sees your anxieties but frees your spirit; recognizes your disabilities but emphasizes your possibilities.” -William Arthur Ward

Editor’s Note: This article was written by Dr. David Mashburn. Dave is a Clinical and Consulting Psychologist, Partner at Tidemark, Inc. and a regular contributor to WorkPuzzle. Comments or questions are welcome. If you’re an email subscriber, reply to this WorkPuzzle email. If you read the blog directly from the web, you can click the “comments” link below.