How did you do on your assignment from last week? I know, when it comes to reengineering your business, it is probably not something you can do over a weekend. If you need to catch-up, take some time to read the last two (1 and 2) discussions.

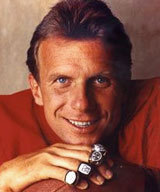

Since it is Super Bowl week, I thought I would spend a little more time talking about a guy who knew quite a bit about winning Super Bowls—Bill Walsh. We learned last week that Walsh decided to question (and later abandon) the status quo for NFL football teams. He did this primarily out of necessity because he didn’t have the resources to play the game like everyone else.

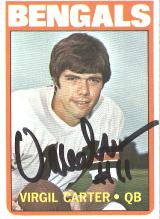

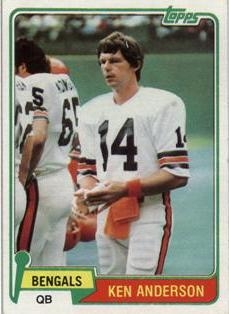

Once he had some initial success with the Cincinnati Bengals, he went on to prove out his theories with three more teams over the next 15 years. Here’s a quick summary:

Walsh left the Bengals in 1976 to become the offensive coordinator of the San Diego Chargers. With the Chargers, Walsh inherited a struggling quarterback named Dan Fouts. Inside of Walsh’s passing system, Fouts led the NFL in completion percentage the next year. Fouts went on to become one of the best quarterbacks in NFL history.

In 1977, Walsh became the Head Football Coach at Stanford University. He only coached Stanford for two years, but experienced quick success, especially at the quarterback position. In 1977, Stanford quarterback, Guy Benjamin, led the nation in passing and won the Sammy Baugh Award given to the nation’s best passer. One might think that was just good luck (i.e. Walsh showed up at the right time), until you notice that in 1978 Benjamin’s replacement, Steve Dils, repeated his accomplishments!

In 1977, Walsh became the Head Football Coach at Stanford University. He only coached Stanford for two years, but experienced quick success, especially at the quarterback position. In 1977, Stanford quarterback, Guy Benjamin, led the nation in passing and won the Sammy Baugh Award given to the nation’s best passer. One might think that was just good luck (i.e. Walsh showed up at the right time), until you notice that in 1978 Benjamin’s replacement, Steve Dils, repeated his accomplishments!

In 1979, Walsh was finally awarded an NFL Head Coaching job—his ultimate goal. However, the team he inherited, the San Francisco 49ers, had the League’s worst record and the League’s lowest payroll. He also had, by most statistical measures, the NFL’s worst quarterback—Steve Deberg. In the previous year, Deberg had a 45.2 pass completion percentage and 22 interceptions.

As usual, quarterbacks seemed to blossom in Walsh’s offensive system–Deberg’s transformation was particularly remarkable. The next year, Deberg completed more passes than anyone in NFL history. His interception percentage dropped by 50% and his completion percentage rose to 60%.

As if almost to prove his point, Walsh fired Deberg the next year and brought in a new college recruit to run the 49er offense. His choice was a third round draft pick from Notre Dame that most people said was too small and had too weak of an arm to play in the NFL. His name was Joe Montana.

As many of you know, Joe Montana went on to become one of the greatest quarterbacks in NFL history. He was the starting quarterback in four Super Bowls in the 1980s, and his team won all four. At this point, you have to start wondering—was he really that good, or did he just play inside a system that allowed him to experience remarkable success?

Michael Lewis, in his book The Blind Side, answers this question:

“How good was [Montana] really? That’s hard to know, because his coach held a magic wand, and every quarterback over whose head that wand passed instantly looked better than he’d ever been. When Joe Montana’s play became sloppy in the 1987 season, Walsh replaced him, temporarily, with Steve Young—whose sensational performance caused a lot of 49ers to wonder, and to feel guilt for wondering, if maybe Steve Young was even better than Joe Montana.”

Of course, Steve Young went on to become a Hall of Fame quarterback himself, but there is even more evidence that Walsh was probably the ultimate star. In 1986, when Joe Montana was injured, Jeff Kemp stepped in as his backup for ten games. In Walsh’s system, Kemp completed nearly 60% of his passes and averaged 7.77 yards per attempt, posting one of the highest passer ratings in the NFL. The same year, Kemp was eventually injured also. He was replaced by a quarterback named Mike Moroski who had only been with the team two weeks before he found himself in a starting role. Even Moroski completed 57.5% of his passes!

There are some who believe that Walsh changed the entire way that football was played professionally. In the late ‘70s, NFL teams passed the ball 42% of the time and ran the ball 58% of the time. By 1995, one year after Walsh retired from coaching; NFL teams passed 59% of the time and ran the ball 41% of the time.

What’s the lesson here? Not many of us are going to be as brilliant and as successful as Bill Walsh, but we can learn from his example. Walsh created a football system that many people (who happen to be quarterbacks) could be successful under. He gave up on trying to “find the best talent” and instead built the best system.

I talk to many business owners and first level managers who mistakenly believe that recruiting a large number of people will solve their problems. In the real estate industry particularly, this is the status quo. It takes a great deal of effort, expense, and focus to execute a high-volume recruiting effort. And yet, these efforts only produce a success percentage of about 15%.

What if some of this effort was redirected toward creating a sales system where 50% or more of the people who operate inside of it are successful? You’ll know you’ve developed such a system when, like Walsh, you can plug almost anyone into the position (who has a baseline set of capacities and competencies) and he/she is successful. This would be a major paradigm switch for the real estate industry. While you wouldn’t make it into the football Hall of Fame for developing such a system, you could change an industry and be remembered as a great innovator in your own right.

Editor’s Note: This article was written by Ben Hess. Ben is the Founding Partner and Managing Director of Tidemark, Inc. and a regular contributor to WorkPuzzle. Comments or questions are welcome. If you’re an email subscriber, reply to this WorkPuzzle email. If you read the blog directly from the web, you can click the “comments” link below.

![Bill-walsh-400[1] Bill-walsh-400[1]](http://workpuzzle.com/~workpuzz/.a/6a010535f94817970b0128770c2ff4970c-800wi.jpg)